by Leslie Webster

When Charles the Great was buried in his great Palatine chapel at Aachen on January 28, 814, it was, according to tradition, in an early third-century Roman sarcophagus depicting the story of Persephone; and he may also have been covered by a sumptuous Byzantine ‘quadriga’ silk, which dates to around AD 800. We can’t authenticate these longstanding traditions, but both artefacts remain treasures of Aachen cathedral today, and both are exactly the kind of thing that Charles himself would have brought to enhance the grand vision of Romanitas that he had created there. Of course, both are rare and costly treasures, appropriate to royal pomp; but it’s also significant that both carry symbolic themes which resonate with the life and death of a ruler: continuity/renewal in the case of the Persephone theme, and imperial triumph and largesse in the case of the charioteer silk. In death, as in life, it seems that the emperor’s power and authority was accompanied by potent signifiers of imperium, from Rome and from Byzantium.

In this rather swift gallop through the topic, I want to look at the ways in which Charlemagne’s construct of a new Roman-style authority and culture was expressed through symbols of religious and secular power which were manifested in court and church: in the dress of the emperor and his magnates, in the great buildings of his reign, in their furnishings and contents, and in the sumptuous liturgical and instructional manuscripts that bear witness to his promotion of learning and of liturgical reforms. This is absolutely at the heart of his renovatio Romani imperii, that decisive mission statement which was cut into Charles’s imperial seal after his coronation in St Peters in 800; but a close relationship with Rome, and an emulation of its imperial past, was already significant for the Carolingian rulers.

Indeed, the close relationship between the Carolingian dynasty and the Church in Rome was sealed in the reign of Charles’s father, Pippin the Short, whereby in an agreement with Pope Stephen, the Carolingian king had become in effect the defender of the see of St Peter; he and subsequently his two sons were anointed kings by the Pope and given the title Patrician of the Romans. Pippin himself is thought to have brought porphyry columns from Italy to grace St Denis, the precious purple marble beloved of Roman emperors; so one may see the start of a deliberate use of symbols of empire in his reign. The Church of Rome needed the Frankish kings as its defenders against external and internal aggression, and they in turn needed the Papacy to validate their authority. Unsurprisingly, Charles and his learned advisors, such as Alcuin, Angilbert, and Theodulf, set about creating a wholly new, and uniquely grand, visual vocabulary for this new imperium.

[1] We’ll begin with the person of Charles himself, and that terrific description from Einhard, which shows that he represented himself in a way rather different from the image of a Roman or Byzantine patrician, and to an extent, also from that of his successors such as Louis the Pious, Lothair, and Charles the Bald. Here’s Einhard:

‘He used to wear his national, that is, Frankish costume. Next to his skin he put on a linen shirt and linen underwear; then a tunic edged with silk and stockings. Then he wrapped his thighs and his feet with leggings, and in winter, covered his chest and shoulders with a jacket made of otter skins or ermine and a blue cloak. He was always armed with a sword, with a gold or silver hilt and belt. Sometimes he used a jewelled sword, but only on great feast days or when he received foreign ambassadors. He spurned foreign clothes, no matter how beautiful, and never wore them except at Rome – when, asked once by Pope Hadrian, and then by Leo, Hadrian’s successor, he wore a long tunic and a chlamys, and put on shoes made in the Roman way. On feast days he would process in a robe woven of gold, with jewelled leggings, his cloak fastened with a golden brooch and with a crown of gold adorned with precious stones. On ordinary days, his dress differed hardly at all from the common people.’

No certain contemporary image of Charles survives, but he must have looked very like the well-known small bronze statue of a Carolingian emperor, possibly Charles the Bald, mounted on a horse:

Fig. 1: Gilded copper-alloy statuette of a Carolingian emperor, probably Charles the Bald, in Frankish dress.

This impression is confirmed by 16th- and 17th-century sketches of now lost or much restored contemporary mosaics depicting Charles meeting Pope Leo III in Rome at the time of his imperial coronation in AD 800:

Fig. 2: Left, 16th-century drawing of the mosiac showing St Peter with Pope Leo III and Charlemagne from Leo II’s triclinium (assembly hall) and Centre, the much restored mosaic today. Right, 17th-century painting of the destroyed apse mosaic from Sta Susanna, Rome, with Pope Leo III and Charlemagne.

We also have archaeological evidence for some of this: the sword belt and fittings that he wore were, if not exactly the garb of the common people as Einhard wrote, certainly standard accoutrements of the aristocratic class, found all across the Carolingian empire:

Fig. 3: Carolingian elite male dress accoutrements: Left, gold brooch from a Viking hoard at Hoen, Norway; Right, spurs and belt fittings from a magnate’s grave in Croatia.

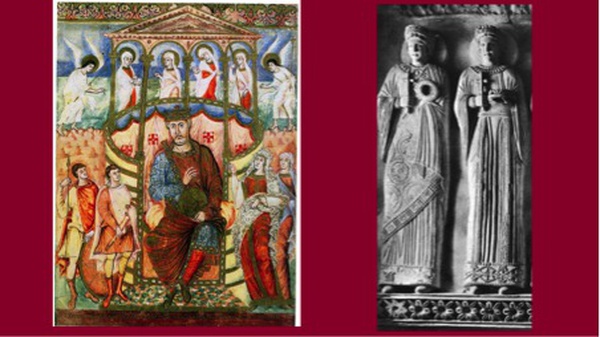

As for the imperial dress he wore on special occasions, though no manuscript portraits of Charles himself survive, images of Charles the Bald and Lothair in imperial manuscripts show what the long tunic and mantle described by Einhard might have looked like.

Perhaps nearer to what Charles might have looked like on feast days and other important occasions is the image of Charles the Bald in Frankish dress in the San Paolo Bible, dated to c 870:

Fig. 4: Left, Charles the Bald enthroned, with Richildis on his left, from the San Paolo Bible; Right, stucco images of female saints from the oratory of Sta Maria, Cividale.

This also has the bonus of showing his wife Richildis - depictions of Frankish women’s dress in this period are rare indeed. The Lombard princess who was Charles first wife might have looked like the beautiful stucco figures of martyrs at Cividale, with their richly hemmed tunics and mantles, although these are somewhat more Byzantine in style.

[2] The equally magnificent backdrops to the splendours of the Carolingian court were the great palace complexes of Charles’ s reign such as Paderborn, Ingelheim, and of course, what came to be his principal residence, at Aachen. With their great halls, the aulae regiae, based on Roman basilicas, and their equally grand royal chapels, these were imposing and ambitious statements of the emperor’s authority.

Paderborn in Saxon Westphalia was built as a symbol of Charlemagne’s power in an area only recently brought under Frankish control. Begun in 776/777, it was here that Charles received Pope Leo III in 799, after the attack on the Pope’s life, the beginning of events that led up to Charles’s coronation as Holy Roman emperor on Christmas Day 800. The palace doesn’t survive today, only the lower parts of the later Ottonian and Salian palace which were built alongside it; but excavations have revealed its scale and nature, and a great deal of information about its lavish decoration. Fragments of painted wall plaster, glass windows, grand inscriptions in the Antique manner, and fine tablewares, including the remains of many glass drinking vessels were recovered, indicating the desire to transplant an image of Roman style grandeur in this recently conquered outpost of Charles’s empire:

Fig. 5: Fragments of painted plaster, window glass, and a reconstructed drinking cup from the Carolingian royal palace at Paderborn, Westphalia.

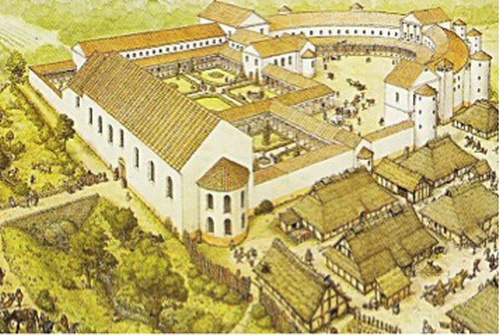

An even more ambitious scheme was constructed at Ingelheim, near Mainz, which was begun before 787:

Fig. 6: Reconstruction drawing of the Carolingian palace complex at Ingelheim, Germany.

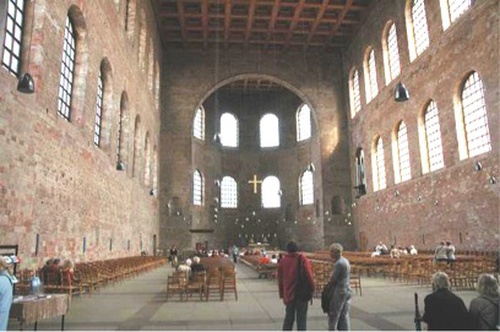

The palace and chapel complex included a grand semi-circular colonnaded ambulatory; feeding this complex of buildings and the vicinity is a canal lined with opus signinum, which had been thought to be Roman, but has been dated by dendro-chronology to the Carolingian period – further evidence of the ambitious plans of Charles and his successors. The grand aula regia, may have drawn upon the aula regia built by Constantine at nearby Trier which, transformed into a grand basilican church, still exists today:

Fig. 7: Above, digital reconstruction of the great aula regia at Ingelheim; Below, interior of the aula of Constantine at Trier.

The palace was subsequently augmented by Charles’s son Louis, in whose reign a grand scheme of wall paintings was added to the aula. These are famously described in a poem written by Ermoldus Nigellus in c. 825/6. The programme was based on Orosius’s History against the Pagans, to which have been added scenes of the Christian conquests of Charles Martel, Pippin, and Charlemagne. The décor was arranged on facing walls, so that the pagan tyrants and heroes (among them Cyrus, Romulus, Hannibal and Alexander) were confronted by what the poet calls the ‘deeds of the fathers who were already closer to the faith’, that is, Christian emperors and kings, including Constantine and Theodosius, as well as the Frankish worthies. A similar programme of oppositions was painted in the palace church, with scenes from the Old Testament on one side and ones from the New Testament facing it on the other, something also described at Aachen. The programme concludes with Charles, who (Nigellus again) ‘shows his gracious face and bears rightfully on his crowned head the diadem; here stands a Saxon warband, daring him to battle – he fights them, masters them, and draws them under his law.’ No trace of these survives today, but we can gain a general idea of their likely quality from the remains of surviving wall paintings of the period, such as those at the churches at St Benedict at Malles and the monastery of St John at Mustair, both in the Tyrol, where evidence for ambitious and highly accomplished schemes can be seen:

Fig. 8: Wall painting of Christ healing the deaf-mute, Abbey church of St John, Mustair, Switzerland.

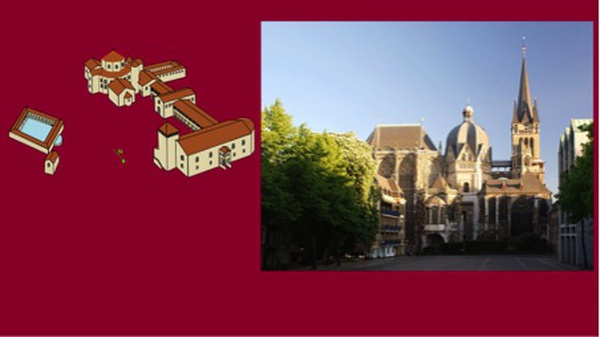

But it is of course Aachen, Charles’s new Rome, which is the ultimate architectural expression of renovatio:

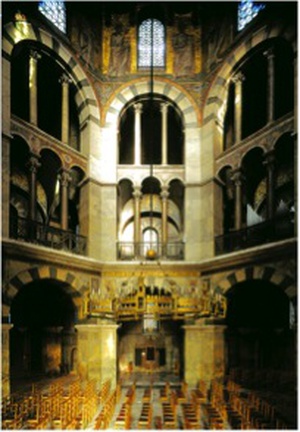

Fig. 9: Left, reconstruction drawing of Charles’s palace and chapel complex, Aachen; Right, the chapel as it is today.

The palace has gone, but the octagonal palatine chapel still survives in its magnificence. Its distinctive form suggests that it could have been inspired by the church of San Vitale at Ravenna, which Charles himself had visited on at least three occasions. This is an imperial statement as well as a grand evocation of the early Christian church. Overlooking the central area from the upper ambulatory is Charles’s throne, perhaps intended to evoke the throne of Solomon, who served as a model of the wise ruler for the Carolingians:

Fig. 10: Left, interior of the Aachen chapel; Right, throne of Charlemagne, looking down over the central area of the chapel.

We are told by Einhard that he adorned the chapel ‘with gold and silver and lamps and with railings and portals of solid bronze’: some of these impressive exercises in the late Antique style can still be seen, and were cast on site nearby:

Fig. 11a: the great bronze doors of Charles’s chapel at Aachen.

In 787 he wrote to Hadrian I asking for "mosaic, marbles, and other materials from floors and walls" from Rome and Ravenna. The original apse and roof mosaics were destroyed in a fire and were recreated in the 19th century; but we know that they included a great image of Christ in Majesty, symbolizing that Divine governance to which all earthly rule is due. This was an ambitious programme, modelled on similar depictions in Rome. Charles also brought other Antique spolia in the form of columns and marble from Rome and Ravenna, and classical statuary, all to create this new Rome that was the palace complex. From Ravenna he also brought an equestrian statue, thought to be of that other great Germanic ruler, Theodoric the Ostrogoth, but which was probably actually of Zeno; this seems to have stood in the court between the chapel and the aula regia. Other late antique bronzes at Aachen which were possibly introduced by Charles include the famous statue of a female wolf or molossus dog; and the pine cone that once adorned a fountain may be a contemporary copy, made in the palace workshop, of a similar pinecone from a fountain at St Peter’s in Rome, accompanied by peacocks:

Fig. 11b: Monumental bronze pine-cone from a fountain in the palace complex, Aachen.

This represented the Christian symbol of the fountain of life, a prominent theme in some Court School manuscripts [see figs. 25 and 29 below].

[3] Other churches and abbeys came close to matching the chapel palatine in splendour: we have for instance, an 11th century account of the monastery church at St Riquier, near Abbeville in N France, which was rebuilt by Charles’s [quasi] son-in-law, Angilbert in 799:

Fig. 12: Abbey of St Riquier, France. Left, 17th-century engraving; Right, reconstructed plan and elevation of the Carolingian church.

One of the largest monasteries of the realm, it had a great west-work, and inside, marble floors; an 831 inventory of its treasury describes numerous liturgical treasures of gold and silver, including altars with canopies of gold and silver and hanging crowns, a marble lectern, many ivories and bookcovers, and a gospel book written in gold, which is almost certainly that given by Angilbert to the abbey and which survives today in the library at Abbeville (a Court School product, c.800).

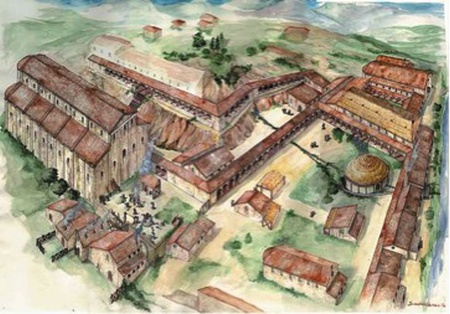

Further afield, recent at the Carolingian monastery of San Vincenzo al Volturno, in Central Italy have also revealed hints of the grandeur of some of these communities; this was one of the most powerful abbeys in Europe, which had been granted fiscal and jurisdictional privileges by Charles:

Fig. 13: Monastery of San Vincenzo al Volturno, Italy; artist’s impression.

Elaborate programmes of wall paintings and decorative wall plaster give something of the flavour of its interior:

Fig. 14: Carolingian wall-paintings and painted plaster from San Vincenzo al Volturno.

The lavish decoration of these grander establishments was also matched on a smaller scale; the private oratory of one of Charles’s most learned and trusted advisors, the Visigoth Theodulf of Orleans, survives (though much restored) at Germigny des Prés. It was consecrated 806, and built in the form of a Greek cross; the heavily restored mosaic of the Ark of the Covenant in the apse represents, at one level, a symbol of Christ, but also evokes the trope of the Franks as the heirs to the Israelites – an important theme for the Carolingians in terms both of temporal rule, and religious authority:

Fig. 15: Germigny des Pres; Carolingian mosaic with the Ark of the Covenant, restored.

The nearby imperial villa equalled this learned splendour with frescoes depicting the seven liberal arts, a map of the world and the four seasons.

It is appropriate also to mention Corvey here, because although it was founded in 822, eight years after Charles’s death, it is one of the great surviving Carolingian monastic icons, with its great west work, and equally impressive, the galleried first floor aula inside it:

Fig. 16: Corvey, Germany; Left, the Carolingian westwork; Right, the interior of the first floor aula.

The familiar arcades of classical columns are here, but this was also elaborately decorated with painted plaster and life-size stucco figures, with their preliminary underdrawings:

Fig. 17: Corvey, reconstruction drawing of the aula, showing the stucco figures.

In the gallery there are traces of wall-paintings with classical themes, including Odysseus vanquishing Scylla, possibly intended as an allegory of Christs’s victory over sin and death. This ostentatious (and learned) invocation of antiquity is matched in the extensive use of marble and porphyry spolia as tiles in the abbey church itself.

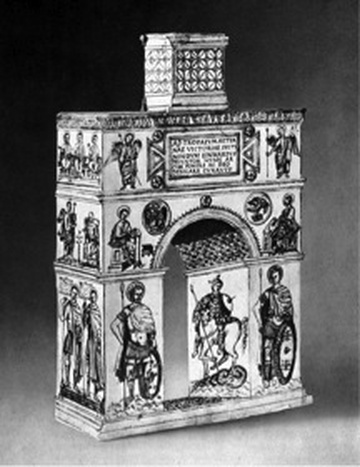

[4] The more portable contents of these structures are largely of an ecclesiastical nature, as they survive today. They reinforce the theme of Romanitas in their style and form, and in the often lavish use of jewels and costly substances such as ivory, silk, and precious metals. Some are extraordinarily ambitious, and inventive. Charles’s biographer Einhard (c.775-840) gave to the church of St Servatius at Maastricht a magnificent silver reliquary inspired by the triumphal arches of imperial Rome, which was surmounted originally by a cross:

Fig. 18: Einhard’s reliquary arch. Above, the 17th century drawing of both sides; lower Left, a reconstruction; lower Right, the arch of Constantine in Rome.

It was destroyed during the French occupation of Maastricht in the 1790s, but a seventeenth-century drawing of it shows how ingeniously it transposes the imperial iconography of Rome to the Christian culture of the Carolingian court. And as the inventory of St Riquier, and the lists of Charles’s gifts to St Peter’s at Rome and to Aachen suggest, the portable contents of these great buildings were of a magnificence to match the architecture. After the mass following his acclaim as emperor and Augustus in St Peter’s, among the gifts Charles gave to the church were: two silver tables; a jewelled gold crown weighing 55lb; a large jewelled gold paten inscribed CHARLES, weighing 30lb, and a large jewelled chalice weighing 58lb. A massive gold table and three more silver tables were left in his will – a silver one with an image of Constantinople, to go to St Peter’s in Rome, another with an image of Rome, to go to the Bishopric of Ravenna; the third, which (according to Einhard) ‘far surpassed the other two in weight and beauty’, showed the plan of the universe in three circles, which probably resembled celestial maps in some contemporary manuscripts; this and the gold table were to go to his heirs, and to alms. Their afterlife was regrettably a short one; they were subsequently broken up in 842 by Lothair, to fund his troops in some internecine strife.

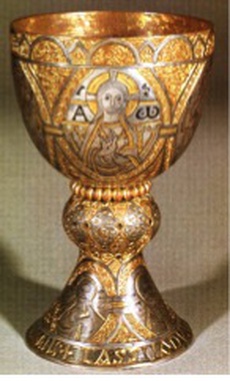

The classical vocabulary of Einhard’s arch, and the tables, is also apparent, in various ways, in altar equipment and reliquaries. There is a marked contrast between the old, Anglo-Carolingian style of the silver gilt chalice of Duke Tassilo of Bavaria, which was given to Kremsmunster Abbey by Tassilo’s wife, Luitpirga, probably on the occasion of the establishment of the Abbey in 777, and two chalices from imperial workshops, the early ninth-century silver chalice from a princely tomb at Kolin, and ivory Utrecht chalice; these are decorated with classical palmette decoration and in the case of the Utrecht chalice, with exuberant acanthus ornament – a very popular motif in Carolingian secular and ecclesiastical metalwork and manuscripts:

Fig. 19: Left, Duke Tassilo’s chalice; Centre, chalice from Kolin, and Right, pyx with acanthus ornament.

Also part of the celebration of the mass are a group of gilded silver altar vessels - pyxes and bowls, also richly decorated with classical acanthus ornament and allegorical motifs.

Another prominent feature of the visual language of the court workshops was the lavish use of precious stones – quite different from the traditional Germanic garnet cloisonné inlays, they often are displayed in filigree-enriched settings to enliven a gold or gilded surface with colour and light:

Fig. 20: Gems and intaglios in Carolingian metalwork. Top Left, and lower centre, the Enger reliquary and the purse reliquary of St Stefan. Lower Left, the ‘Talisman of Charlemagne’; top centre, intaglio gem with bust of Lothair; Right, front cover of the LIndau Gospels.

Some were given even greater prominence, such as the sapphire in the so-called Talisman of Charlemagne, or, somewhat later, the many gems set in openwork or as pendants on the Escrain of Charles the Bald, and the great rock-crystals with intaglio decoration:

Fig. 21: Rock-crystal engraved with scenes from the biblical story of Susannah and the Elders; made for Lothair II (AD 855-869).

Their symbolism might be linked to the gems of the heavenly city described in the Apocalypse, and to antique gem lore, but in their costliness, and their profusion, they reflect a late Roman tradition. Ancient cameos and intaglios were particularly prized and imitated, even in manuscripts [see figs. 20 above, 29 below].

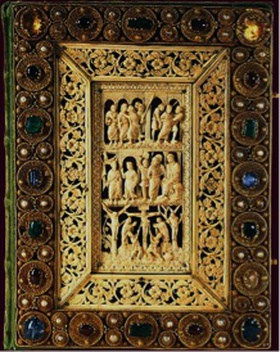

[5] As precious as gold and gems, ivories were another significant product of the Court Schools of Charles and his successors. Elephant ivory was a rare luxury, and many Carolingian ivories re-use late Antique diptych leaves. They also adapted the style and conventions of antique ivories and introduced not only a new form of religious artefact to the west, but new concepts of figural depiction, and of the use of space. Two relatively early examples of Charles’s Court School ivories appear on the cover of the Dagulf Psalter (c. 788/91) and a diptych from Bourges, perhaps a little earlier:

Fig. 22: Ivories from Charles’s Court School. Left, panels with scenes from the life of David from the cover of the Dagulf Psalter; Right, diptych with the four Evangelists from Bourges.

The magnificent covers of the Lorsch Gospels were also produced in the imperial workshops; their formal and stylistic debt to consular diptychs is very apparent [fig. 23a, b]. A panel depicting St Michael is another Court School product closely related to the Lorsch Gospel covers [fig. 23c]:

Fig. 23: (a) Left, Consular diptych of Anastasius, AD 517; (b) Centre, back cover of the Lorsch Gospels, early 9th century; (c) Right, ivory panel with St Michael, early 9th century.

This new style continued to develop in distinctive ways in the centres favoured under Charles’s successors; see, for example, the mid-ninth-century ivory with the baptism of Clovis from Reims, and the ivory panels with scenes from Christ’s passion from the front cover of the Gospels of Bishop Drogo of Metz, which date to 845/55:

Fig. 24: Left, Ivory with the Baptism of Clovis, Reims school; Right, cover of the Drogo Gospels, Metz school.

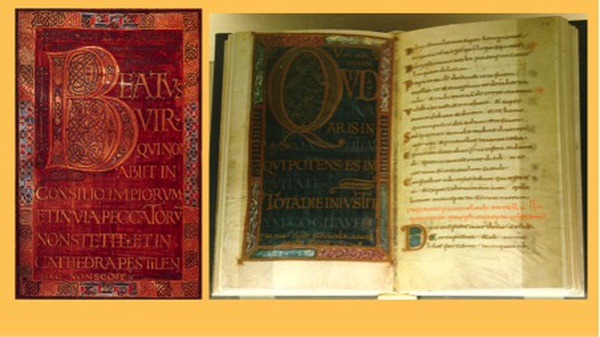

[6] Finally, we come to the manuscripts which lay at the heart of Charles’s renovatio. Always interested in learning, in recording texts, and in making things right, Charles, with his advisors, wanted to promote and circulate correct, revised versions of the Bible and other liturgical texts; he saw it as part of the business of the Holy Roman Emperor to commission proper texts in splendid editions. Scientific and other learned treatises were also copied from late Antique texts. A legible and elegant script, the so-called Caroline Minuscule, was developed for this, and a whole new artistic vocabulary, based on late Antique exemplars far removed from earlier Merovingian or Insular models of Biblical illumination. As we’ve already seen with the wall-paintings and ivories, a subtle, indeed sometimes astonishing, illusionistic treatment of figures and space, together with an array of classical architectural and decorative motifs such as acanthus and other foliage, changed the character of how the Christian message was expressed, from provincial to Imperial. The use of gold and silver lettering and embellishments, and of the imperial purple in so many of these manuscripts alluded to both Divine Majesty, and to the imperial vision.

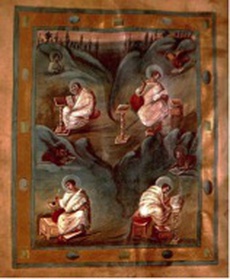

The oldest surviving manuscript from Charles’s Court school is the Godescalc Evangelistary which was written in 781 at the emperor’s command – a dedicatory verse describes Charles as Consul:

Fig. 25: The Godescalc Evangelistary, AD 781. Left, St Mark and St Luke; Right, the Fountain of Life.

Though this is a revolutionary manuscript in so many ways – in its use of naturalistic Italo-Byzantine models, purple stained pages, golden lettering in the classical manner, and new iconographies such as the fons vitae – the awkwardness of the Evangelist figures suggests that this is an early exercise in the manner. The slightly later Dagulf Psalter, made c. 788/91 for presentation to Pope Hadrian VII, shows a different aspect of these early Court School manuscripts – a continuing Insular influence in its interlace, alongside a fully formed version of Caroline miniscule and display script:

Fig. 26: The Dagulf Psalter, AD 788-791.

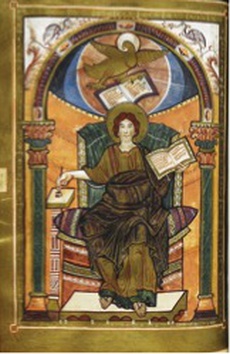

The fine David ivories from its original binding were mentioned earlier [see above, fig. 22]. From the end of the eighth century, the St Denis Gospels with its sumptuous use of purple, gold, and silver, and classical motifs, illustrates a further absorption of late Antique tradition, also represented in the ivory of the risen Christ from its original binding. The early 9th century Lorsch Gospels is another magnificent product of the Court School; its sumptuous decoration is matched by the quality of the ivories from the cover [see also above, fig. 23]:

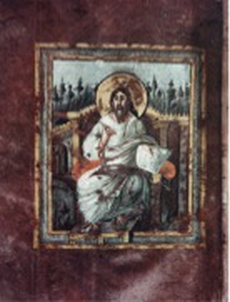

Fig. 27: The Lorsch Gospels, early 9th century; Left, St John; Right, Christ in Majesty.

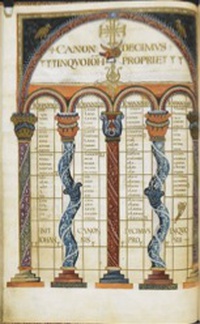

It belongs with a group of other Gospel manuscripts, in which a confident mastery of late Antique form, coupled with an imperial grandeur exactly and powerfully express the idea of renovatio. The twisted Salomonic columns in the Harley Golden Gospels, which date to the late 8th century, show another aspect of the kind of borrowing from Rome that infuses these manuscripts; they are copied from late Antique columns which formerly adorned the altar of St Peter’s, above the burial of the saint:

Fig. 28: Left and centre, the Harley Golden Gospels, late 8th century; St John, and canon tables; Right, late Antique Salomonic column from St Peter’s, Rome.

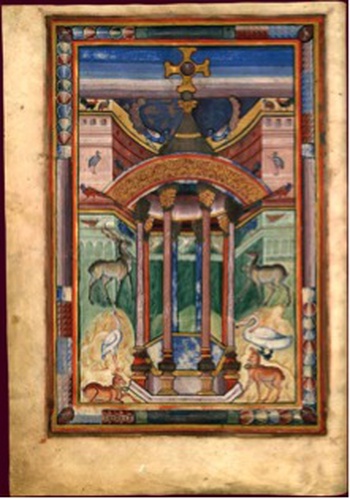

The same Roman motif appears in the Gospels of St Medard of Soissons of c AD 800, where imitation classical intaglios are also painted in the corners of the Fountain of Life page. In its subtle use of illusion, its clever play on space in the Heavenly City, and its beautifully naturalistic creatures around the Fountain of Life, this manuscript is a masterpiece of the fully developed Court School style:

Fig. 29: the Gospels of St Médard of Soissons, c AD 800; Left, the Fountain of Life; Right, canon table with twisted columns.

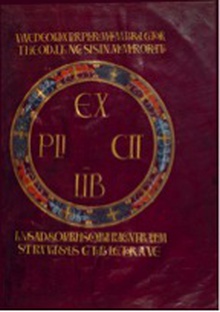

There is a great deal more to be said about the manuscript art of Charles’s reign than this brief overview allows; but I want to close with some contrasting images which sum up the remarkable vitality and range of the manuscripts (and indeed other artistic products) produced in his Court ateliers. The first is of the so-called Coronation Gospels, which, according to tradition were found in Charles’s tomb when it was opened in 1000, though this may be a later invention. Along with a leaf in Brussels, and the Aachen Treasury Gospels, it represents a small group of early ninth-century Court School manuscripts which, though produced at the same time and in same milieu as some of the other great Court School Gospel books, reveal very different influences at work in the imperial circle [fig. 30a and b]. The illusionistic Evangelist portraits, floating against classical backgrounds are based on the portraits of ancient philosophers from late Antique manuscripts, a wholly confident assimilation of a late Antique topos to a Christian message. And yet only a few years later, Theodulf of Orleans was to commission a severely grand bible without any hint of figural representation [fig. 30c] – the stylistic contrast could hardly be stronger:

Fig. 30: (a) Left, the Coronation Gospels, Court School, early 9th century; (b) Centre, the Aachen Treasury Gospels, early 9th century; (c) Right, Bible of Theodulf of Oreans, first quarter of the 9th century.

That the very different and innovative styles illustrated in these manuscripts were encouraged to develop and flourish in the circles of Charles and his advisors is one of the most remarkable aspects of Charles’s renovatio Romani imperii, and a testament to its power. The material culture of Charles’s reign, both secular and ecclesiastical, vividly embodies the vision of a Christian imperium which was manifested in many other ways throughout his rule. In their different ways, these buildings, books and precious artefacts are all potent signals of the new ways in which church and state were shaping the identity of Europe in the early middle ages.